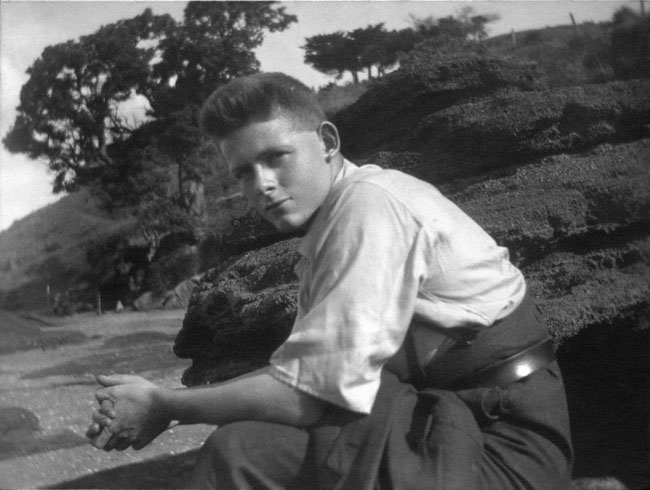

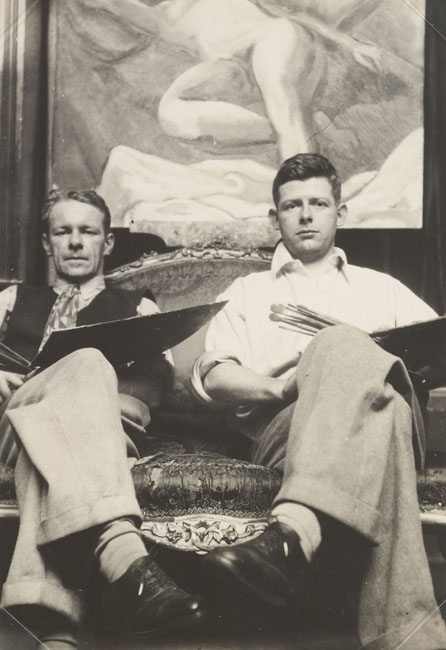

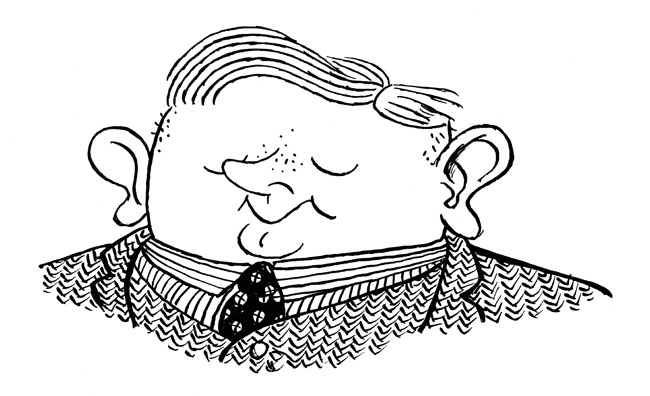

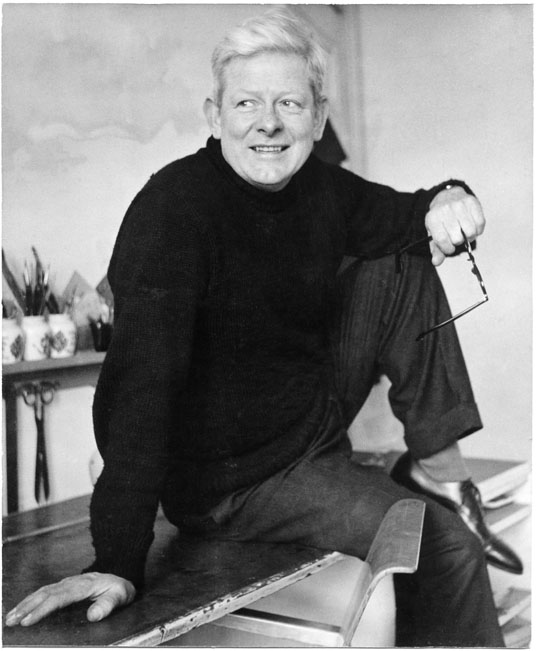

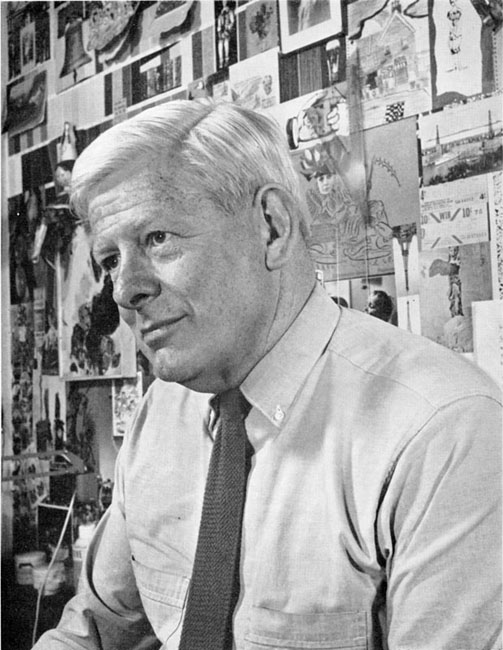

James Boswell, a genial, good humoured, prematurely white-haired, generous New Zealander, born in 1906 of Scots/Irish descent, the son of a schoolmaster. He came to London in 1925 to study at the Royal College of Art, hated the dreary, academic atmosphere and decamped to a mentor, Freddie Porter, who taught him about modern painting. The RCA threw him out, not once but twice which could be some sort of record. Freddie Porter continued to be a mentor and he painted steadily until 1932 when he stopped and took to graphic art, believing that his talents could be used to good effect in the cause of his political beliefs.

When he came to London he was horrified by the squalor and poverty he saw around him and, determined to do what he could to help and encouraged by Montagu Slater, he joined the Communist Party, threw himself wholeheartedly into left wing politics and with a group of like-minded artists, launched the Artists International Association (AIA) in a bid to help the plight of the poor and to oppose the creeping rise of fascism. He painted banners, designed leaflets and supplied illustrations and cartoons to any appropriate publisher who would use them. He joined the CP in 1932 and failed to renew his membership in 1943, disillusioned by where the party was heading but he never lost his faith in Marxist principles.

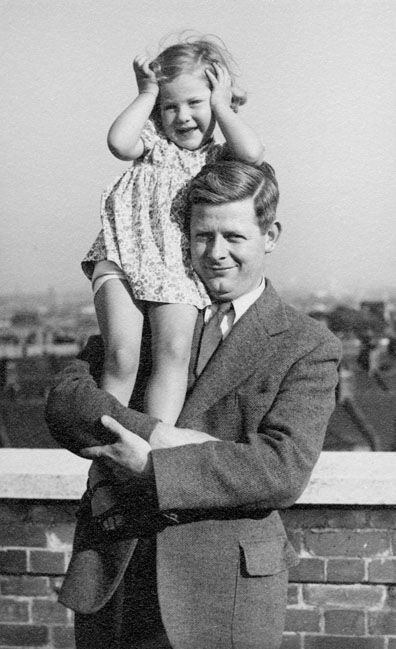

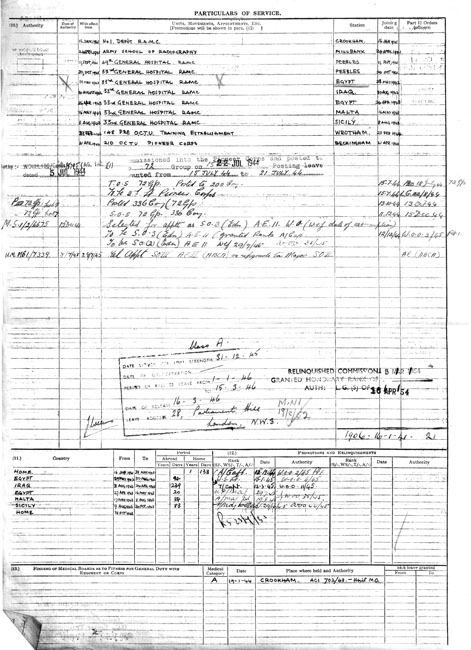

With James Holland and James Fitton he gloriously revived the tradition of social satire in English illustration in the magazine Left Review. In 1934 he married Betty Soars and in 1936, in order to eat, pay the rent and finance the baby who appeared, very much loved but inconveniently timed, he went to work for Shell in the publicity department and was still there when war broke out. He spent a year on the roof with the ARP doing fire duty, was called up in early 1941 and trained as a radiographer. As soon as he was enlisted he began to record everything he saw and thought and, unencumbered with the label ‘Official War Artist’, he didn’t have to produce the positive images which the Ministry of Information wished the general public to see but could draw everything, however negative. In 1942, was sent to Iraq where he remained, bored, angry at the stupidity of war, hot, dusty and exasperated. During this time he drew a number of savage, anti-war, satirical drawings which have been compared to Goya’s Disasters of War and are now in possession of Tate Britain. He spent all the time he could filling his sketch books and he taught his companions how to draw. In mid 1943 he returned slowly to England via Malta and Sicily, was commissioned and went to work for the Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA) producing pamphlets for the forces telling them what to do when the war was over, a job they did with such efficiency that ABCA were credited with having ensured the Labour Party were elected in 1945. When the war was over, he went back to Shell.

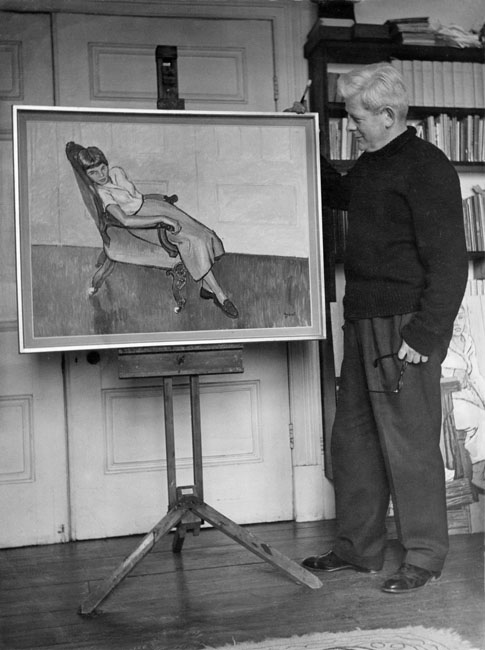

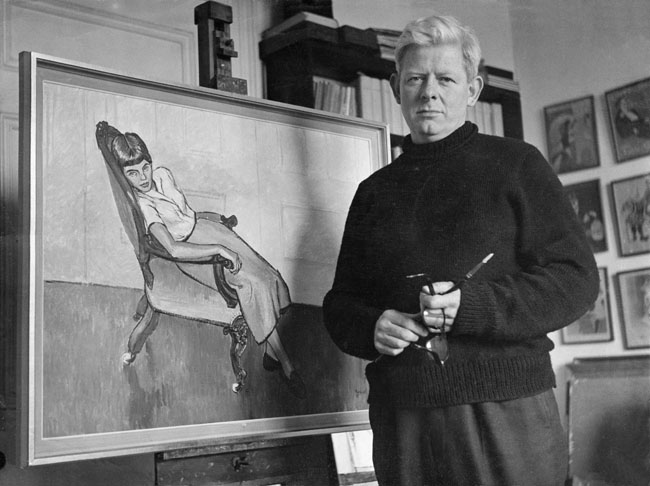

In 1947 he wrote The Artist’s Dilemma in which he explored the problems which beset artists who have to work commercially in order to be able to afford to paint and draw as they might wish. He wanted to paint but getting going was proving difficult. When he left Shell in 1947, he became art editor of Lilliput, a small, popular, literary magazine which employed outstanding writers, photographers and artists and he spent three years there having a thoroughly good time until the proprietor pulled the plug. In 1951 he painted a huge mural for the Sea and Ships Pavilion at the Festival of Britain. The dilemma of requiring an income still loomed; he needed to finance his life style and his ever-present urge to get back to painting.

Sainsbury’s came to the rescue. They needed an editor for their house magazine, so James took to grocery part time and when he wasn’t investigating the manufacture of vinegar or the history of the Aberdeen Angus and illustrating everything as only he could, he was in his studio discovering again how to draw and paint. In 1957 he and Betty moved disastrously to Hove in Sussex. He loved the coast but not permanently. He was a Londoner and the commuting destroyed him. He rented a flat in Paddington and spent more and more time in London. In 1964 he helped the Labour Party win the General Election with posters and advertisements which he seemed to be creating single-handedly, his room full of shears, coloured paper, Cow gum and thumbs-up signs, He painting steadily and powerfully and was drawing beautifully. In 1966 he left Betty and set up home with Ruth Abel, his assistant, companion, champion and partner for the last nine years of his life. He died, far too early aged not quite 65 on 15 April 1971.

Sal Shuel

Close ✖