Brian Shuel remembers Jim Boswell

I met James Boswell’s daughter Sal in January 1954 the very first day I arrived at the Central School of Art in London. A green-as-grass eighteen-year-old from Ireland, covered in confusion in strange surroundings, in a life drawing class with a naked lady I was actually encouraged to look at, must have appealed to her maternal instincts for she took me under her wing and we have been together ever since.

My childhood is, of course, another story though it wasn’t particularly unhappy. Nevertheless, when I arrived in London I was looking forward to beginning a whole new life, though I hadn’t realised that what I needed was a family...

Enter the Boswells. It wasn’t long before I was absorbed into their circle bewitched by their ‘bohemian’ way of life, so different from Anglo-Irish convention where ‘art’ was something to be discussed in whispers. It soon became apparent that Sal and I were in earnest, which her mother Betty accepted with enthusiasm. Apparently she thought I was well brought up, polite, fairly clean and reliable, and didn’t talk too much, just what Sal needed. On the other hand Jim, Sal reported, thought exactly the same things, which were evidently just what Sal didn’t need. Who was going to be good enough for his little girl?

He was right, of course. Well, they both were. But Jim Boswell never once showed the slightest antagonism towards me. Perhaps he figured that I would be fine for the time being but would surely be history before long. Meanwhile he was happy enough to have an acolyte at his feet. I was much too shy and in awe to get close but I did find out he had been art editor of the legendary (but recently closed) Lilliput magazine, that he had done Ealing film posters and illustrated well-known books, that he was an interesting, but unpredictable painter. At that stage I knew nothing about his pre-war Left Review work, his war drawings, his AIA lithographs. Still I could appreciate that he was an amazingly versatile and professional illustrator and indeed I regarded this as his prime function. His paintings seemed to me complex versions of his illustrations. The most important thing to me, though, was that he was such amazingly good company.

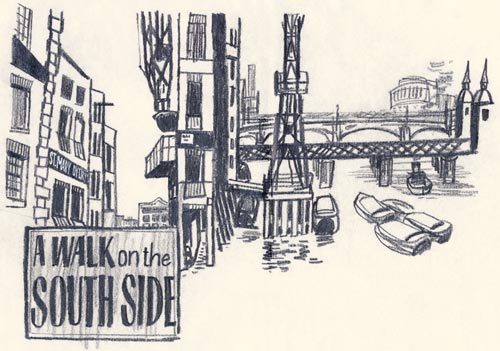

Still, there was one thing I really didn’t understand about him - which eventually turned out to be what cemented our friendship. Jim was the editor of Sainsbury’s house magazine, which seemed bizarre for a distinguished artist and man about town. I suppose it suited him; it paid well and left him plenty of time to do whatever else he wanted. I have since discovered that Sainsbury’s just asked him out of the blue. They can have had little idea what they were actually going to get. ‘JS Journal’ was an entirely new venture for the company and Jim came up with a pocket magazine (not totally unlike Lilliput!), full of company affairs it is true but also fascinating features about food production (on a huge scale much more interesting than you might think), well researched histories of the towns where new branches were to open, but also items more tenuously related to the grocery business - a series of extracts from the eighteenth century diaries of the food-obsessed Parson Woodforde were memorable. The thing that set JS Journal apart was that it was lavishly illustrated with his own drawings. As house magazines go it was in a class of its own. He did grumble about it from time to time but he he was quite proud of JS Journal which he edited for the rest of his life.

In 1960 Jim unexpectedly asked me if I would like to be art editor – which sounds grand but simply meant doing the page layouts and marking up the pictures. Still, I was reasonably qualified, with a graphics diploma and experience in advertising and a design group. Any hint of nepotism could be countered by pointing out that there were no less than seven Sainsburys on the board at that time! This was a wonderful opportunity for me to go freelance, not only as a designer but also as a photographer, an obsession that had emerged on National Service. I could learn on the job – and the best lesson I had was from Jim Boswell. Having handed him a more than usually poor set of pictures, accompanied by many pathetic excuses, he said kindly ‘Don’t worry, my boy, I’ll put all that in the captions’!

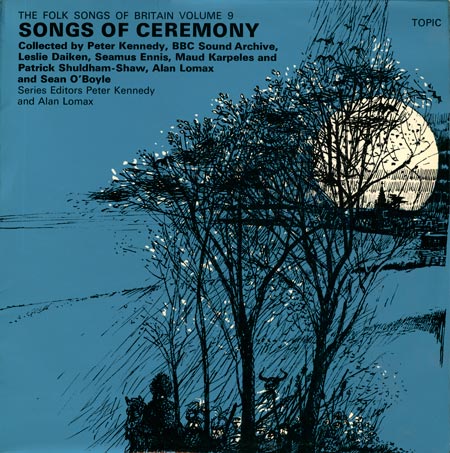

From the late fifties Jim Boswell was also involved with Topic Records. Topic was started by the Communist Party in 1939. By the fifties it was still very left wing but more to do with authentic ‘folk’ music than political propaganda. The company survives to this day, claiming to be the oldest independent record label in the world, indeed 75 years old in 2014. Because of his socialist credentials Jim was invited onto the board of trustees - so that he could produce all their sleeves and publicity material absolutely free! He knew nothing about folk music but, typically, he treated this apparent chore with good humour and complete commitment for the rest of his life. His early sleeves were entirely graphic but by the early sixties he was beginning to feel he should find out what was actually going on in the folk world. He suggested a voyage of discovery which, as a budding photojournalist, seemed to me a great idea for a magazine story...

In the autumn of 1962 the two of us set off on a major tour of England and Scotland to ‘dig the scene’(as the vernacular had it). A diversion to the Aberdeen area on behalf of Sainsburys looked after the travel expenses. The trip was a crucial experience for me (again, that’s another story) for it was the beginning of a lifelong interest in folklore and customs. On Boxing Day 1966 we persuaded Jim to see his one and only folk custom, when he was amazed by the Marshfield Mummers. The unique results are above but in that autumn of 1962 we had a great time, met lots of interesting singers and folklorists and Jim filled a sketchbook with folksingers - but came nowhere near turning into a folkie. Still, for the next decade he used this material and thankfully lots of my photographs on Topic sleeves. His last, and best, LP covers featured his own illustrations for their influential ten volume series ‘Folksongs of Britain’, recordings of genuine ‘traditional’ performers, subsequently much plundered by ‘revival’ singers. We have several of the original drawings in our possession to this day, but my great magazine spread never came to pass!

If you think all this is more about me than James Boswell it is not intended to be. I'm just trying to convey the effect he had on people. Everybody loved him, men and women, artists, printers, grocers, folkies – well, maybe not fascists and certainly not Betty when he went off with Ruth. He was generous with his time, advice and encouragement, though he always claimed that the one thing he could never do was teach. All I can say is he certainly taught me a lot...

Brian Shuel