The Unofficial War Artist by Richard Cork

The most familiar images of the Second World War by British artists are melancholic and reflective. Henry Moore’s tube-shelter series is so determined to avoid overtones of panic or claustrophobia that its Blitz refugees appear embroiled in a sleep profound enough to last through even the most terrifying bomb attack. Paul Nash’s shattered carcasses of German aircraft are caught up in a comparable slumber, as they float on a sea of listless metal fragments washed by an Oxfordshire moon. And the scenes of devastation recorded by Graham Sutherland in the East End, or by John Piper in Bristol and Bath, likewise concentrate on the elegiac aftermath of destruction. There is compassion in Moore’s huddled figures, and implied protest in Sutherland’s twisted girders, but they are all held in a meditative balance between still life, still death.

To find an artist who offers an antidote to this funereal consensus, and has no qualms about hitting out with Goya-like venom at the insanity and viciousness of war, it is necessary to look beyond the charmed circle patronised by the official War Artists’ Committee. The men I have already cited approached the conflict as civilians, and however close they may have come to witnessing its effects at home, they were still at pains to reconcile these disturbing experiences with their previous work: Moore’s reclining sculpture, Nash’s surrealist landscapes, Piper’s architectural topography. Whereas James Boswell, whose outspoken condemnation of the war in a remarkable sequence of drawings has been overlooked for too long, did not have any elevated notions about his status either as an artist or an enlisted soldier.

The private nature of the sketchbooks which Boswell felt compelled to fill, in a ferocious burst of activity during his first two years of army service, doubtless helped him to be completely frank. Since no Committee was ever going to vet his responses to the war -let alone purchase his work or encourage him to carry out an official project - he was free to denounce it in the most corrosive manner imaginable. But Boswell’s isolation from the favoured artists of the period was not simply an accident, the negative result of a failure to gain recognition as an artist during the 1930’s. It stemmed from a very positive determination to define for himself, soon after he left the Royal College of Art in 1929, a role very different from the orthodox notion of the “fine artist”. By 1932, when the Depression was at its most severe, he had decided to give up painting and concentrate on illustration and graphic design, most of which was strongly in sympathy with the ideology of the Communist Party he had just joined.

With considerable fervour, Boswell identified himself throughout that decade with the group of artists who joined him in founding the Artists’ International in 1933. He later remembered that the A.I. was originally supposed to be called “The International Organisation of Artists for Revolutionary Proletarian Art”, a title which aptly summarizes the group’s hatred of Fascism, Imperialist war and Colonial oppression, and its pro-Soviet belief that art should be a weapon of the working class in the struggle against the bourgeoisie. The militant propagandist and exhibiting activities of the AI, which was subsequently renamed the Artists’ International Association, has become a largely forgotten episode in the history of modern English art. Bourgeois art historians tend to ignore it altogether, in favour of the far more well-known avant-garde triumvirate of the 1930’s: Moore, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. But the truth is that England did possess, in the AIA, a surprisingly radical spearhead of artists on the far Left, and a reassessment of their attempts to formulate a Marxist function for art is long overdue.

Boswell’s own work made its greatest impact through the cartoons he contributed to the Left Review, whose first editor, Montagu Slater, wanted to “bring writers into touch with . . . the class struggle.” Boswell’s contributions, a hard-hitting series of polemical attacks on bloated capitalists, repressive conservatives, Fascists and exploiters of the working man, certainly coincided with Slater’s aim. Using a vivid style situated halfway between the Expressionism of George Grosz and the cartoon journalism of David Low, he placed his art firmly at the service of political rebellion.

By the time the Second World War was declared, however, it was no longer so easy to espouse the radical cause. The bitter legacy of Spain had provoked widespread disillusionment among the English Left; the 1939 Soviet-German pact made it initially very difficult for Communists to support the war; and Boswell’s own innate gentleness, which had also expressed itself during the 1930’s in surprisingly mellow drawings of street life which were far removed from the savagery of his Left Review illustrations, became more prominent in his work. In later life he was to separate his art from politics altogether, according to the most familiar English tradition, and the cutting edge of his earlier work became increasingly blunted.

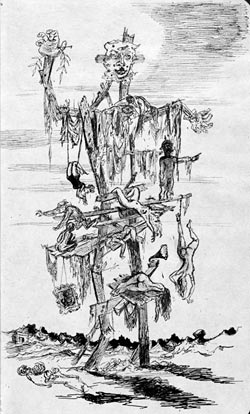

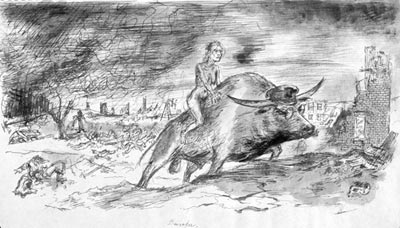

Only for two years after he was called up in 1941 and trained in the RAMC. as a radiographer, did he recover the impassioned urgency of his 1930’s cartoons and bring that side of his art to an unforgettable climax. Three small sketchbooks, packed with drawings so intense that Boswell’s nib constantly threatens to carve through the thin paper, suddenly allegorise the war as a bestial farce conducted by bulls. These Orwellian animals, often dressed in generals’ uniforms, heave their obese bulk through page after page. They ride on the backs of exhausted Tommies, pause with a watering-can to sprinkle a flower-pot containing the grotesquely dismembered skeleton of a soldier, and sit on a hideous pile of corpses and ruined buildings while they type out a mass of documents which sail ridiculously into the sky. Sometimes they play at doctors and press a telescope to their ears in order to inspect a truncated, headless body held up with callous unconcern by two horned orderlies. And then they turn into bespectacled priests who ram a huge graveyard cross into a helpless soldier’s mouth.

The flow of imagery is as prodigal as it is remorseless, suggesting that Boswell treated these sketchbooks as a cathartic outlet for all his deepest loathings of war. The bull idea may have originated in the Rape of Europa myth, for several drawings show a haggard female nude clinging onto the animal as it charges through devastated, burning cities. But it also links up with the derisive army expression “a load of old bull” and most degradingly of all - with the bullshit which streams out of the animal’s hindquarters to fill a sea where soldiers flounder or drown in excrement. Two years later Boswell wrote that he wanted “to extract the dream reality, to evoke the unreality of the soldier’s life.” And I know of no parallel in English art for Boswell’s ability, as a man who paradoxically spent all his army service away from the front line, to expose and denigrate the senseless waste of a conflict which “official” war artists approached with such muted emotions.

Originally printed in the exhibition catalogue ‘James Boswell, Drawings, Illustrations and Paintings’, Nottingham University Art Gallery, November 1976