Cable Street — A Demonstrators Impressions

The carriage was very full for a Sunday Eastward journey. It wasn’t a Sunday crowd. There were no children, and when at Blackfriars the carriage packed up tight with Fascists, the feeling got a bit tense. Some of them wore the new jack-booted uniform with military jackets and riding breeches, looking like stage soldiers. They whistled their songs, but on the whole everyone was quiet and a little nervous.

At Mark Lane* M. and I followed a small crowd, mainly Fascist, across Tower Hill. There is a little excited shouting and laughter among the Blackshirts, and a lot of saluting. The police have already cleared Royal Mint Street for the Mosley parade. We heard there had been charges, but the crowd is very quiet. There is no cheering, no booing, only a very sullen murmuring mass of people standing in the hazy autumn sunshine looking down the street. The parade is assembling around the corner out of sight.

We moved on to get East of the parade. At the foot of Mansell Street there is a very different crowd, noisy and talkative, rows of police beyond them, and everywhere little knots of people arguing and talking. The hum of excited conversation fills the street and buzzes under the railway bridge. All that afternoon everyone was talking. Then I lost M. in the first police charge. We had turned up to Aldgate when we heard shouts, and I looked round. There was a confused movement in the crowd, and beyond that the mounted police were riding forward in a glitter of sunshine. Suddenly, they were in the shadow under the bridge, and the crowd was running and shouting: “To Cable Street. Round to Cable Street. We’ll stop them there.” I looked around for M., but could not see him. Then the police got uncomfortably near, and I ran down a long straight street between high warehouses and the railway.

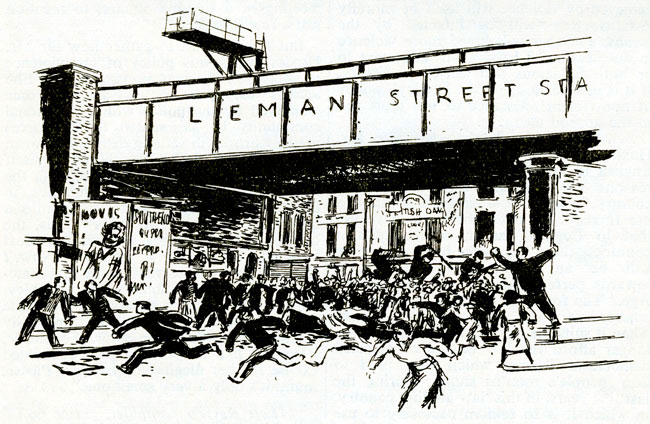

Panting, we come out at Leman Street; no Blackshirts here, but a scuffle is going on at the foot of Cable Street. Hooves clatter and echo under the bridge. The crowd breaks and runs, then re-forms, and is broken up again by short, brutal charges. Four policemen are dragging a half-unconscious boy along the cobbles. Under the bridge at Cable Street the crowd gathers again. It is difficult to say if they are more excited or less excited than at Mansell Street. Certainly they are more determined, more angry. They chant in unison, “THEY SHALL NOT PASS, THEY SHALL NOT PASS.”

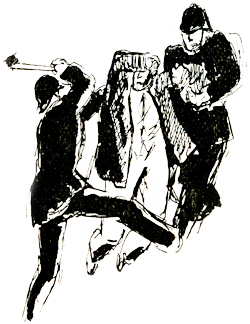

Round the corner a sudden rush of feet, and men and women come running before the police batons. They are clearing the way for another arrest. Two policemen are wrestling with a young boy. His face is streaming with blood, and behind them an inspector jumps about, truncheon raised, trying to get in a blow. The boy is shouting, “Unity, unity, unity, unity.” It is the word of the day. Under the blows of the police and the provocation of the Blackshirts the East End is being welded into a solid, united mass with a single idea—Mosley shall not pass. The police finally get their man away. It took about fifty of them to make one arrest there.

We dodged about, hopping up on the pavement and found the public lavatory, and the piles of the railway bridge that seemed to hang over the whole of that afternoon. It runs high along behind Cable Street and shadows the foot of every side street. You come upon it unexpectedly, lose it, then find yourself once again under its shadows.

The crowd re-formed in Cable Street. Out of side alleys and yards they filter back quite quickly. Later in the day the police cordoned off the streets as they cleared them. Earlier though, they either had not enough men or else had no idea of what they were trying to do. Certainly they miscalculated the opposition, and even later when thousands more had been rushed to the district they were still there on the tolerance of the crowd. A tolerance which lasted only so long as Mosley remained bottled up in Royal Mint Street.

In the middle of Cable Street a boy brandishes a penknife. Immediately he is surrounded by a dozen people, expostulating, arguing “Put it away. We want none of that here,” and “You ought to be down there with the rats.” He pockets his knife and goes off looking a little foolish.

Soon it was quiet again. The shouting stops when the police withdraw. Only the interminable argument goes on.

Leman Street is charged with electrical feeling like a cat’s back. Sudden runs and rushes up and down the street, continual discussion.

“Why don’t they arrest the Black-shirts?”

“Ah, now you’re asking.”

“To his own house they wouldn’t let him go. And he lives there.”

At the station there is a posse of police on the pavement. People are continually being dragged inside. Now and again a few police come out grinning and set off up and down the street. At the pavement edge a few police cars and a couple of vans, too obviously anonymous for even Mr. Drage*. Half-a-dozen hard-faced bigshots in peaked caps stroll up and down.

Gardiner’s Corner is a solid press of people. Packed tight from Woolworth’s to Gardiner’s to Kritch’s, right round to the Underground workings, and back to Woolworth’s. The crowd is very indignant at the behaviour of the police. Indignant in that blunt, obstinate English way.

“We pay rates here,” they say. “We can stand here. Yes, we pay rates for your kind to ride about on horses.”

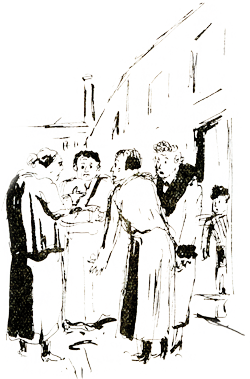

They are surprised, too, for many had expected protestations. On the fringe of the crowd the same talkative, arguing knots of people. “Almost without exception they are asking: “But why? Why? Why are they arresting us? Why, when we pay them to protect us? Why don’t they arrest the Blackshirts?”

Here and there a political discussion is going on. A young Jew is telling how Hitler came to power. Expounding the lesson of unity and the danger of the Labour Party’s attitude. “In Germany again and again the Social Democrats repressed the United Front. And then, even after Hitler was in power . . . .”

An old Jew merely shakes his head from side to side, very sad and very disillusioned. Hitler had seemed a long way away—once.

People come and go. Arrests are frequent. The mounted police edge the buttocks of their horses into the pavements. There is a crash across the street, a few screams, and some laughter. Kritch’s window is broken. Later, I heard that a policeman smashed it with a truncheon blow intended for a too nimble demonstrator.

A young worker is astride the cross-bar of a lamp-standard outside Woolworth’s. On the top bar he ties a length of bright red cloth, and thousands of clenched fists go up with a roar from the crowd, THEY SHALL NOT PASS. He stops up the standard, laughing, and jeering at the police.

Down the back streets the sundry groups of women are gossiping on their doorsteps. It might be any Sunday except that as you pass. you hear the same argument, the same angry question: “Why did they let him come down here at all? And the police?”

In Aldgate the crowd are perched high up on the Underground workings and on the wooden railings at the pavement edge. I thought I had found a place to climb up between two men, but the rail smashed neatly in two as I put my weight on it and I found myself standing between two rather disgusted Jews who had been having a good view. A woman snapped at one of them: “There, I told you it wasn’t safe. You never ought to have stood on it.” I left.

All down Aldgate the same tense, expectant air, the same gesticulating groups in conversation. Someone says: “He’s still in Mint Street. They haven’t made a move yet.”

I looked at the clock. It was three. Only a little over an hour I had been in the East End and it felt like a whole day. All that afternoon, time seemed quite vague and the confusion of clocks made it even more curious*. Where they had been altered it would be three o’clock, so that you seemed to be running also in to a fourth dimension that worked arbitrarily in both directions. Occasionally it felt as if you had been in the East End for several days.

A tough little man was hanging out of a taxi window, talking to himself. “I’d give a pound to get through this. I didn’t ask Mosley down here. You think I’ll get through, brother?” he asked me.

“Not this side of half an hour.”

The cabman settled down with a resigned smile and the tough little man looked up the road and said:

“So many people, Jesus! When did you ever see so many people?”

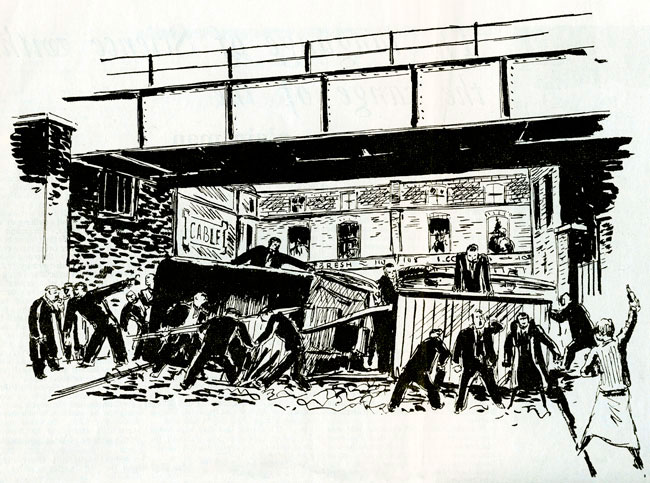

Back in Cable Street, by back streets, I nearly fell over the first barricade as I came out of Back Church Lane. There it was, a big yellow lorry, bang across the street and piles of boxes and lengths of timber, broken glass all over the cobbles in front of it. Then round another alley and down Christian Street. By the little black-and-orange local cinema plastered with bills a crowd of people, is walking to and fro. At first it looks chaotic, but after watching for a few minutes the impression sorts itself out. A greengrocer’s cart and then another one are being dragged rattling over the cobbles by a score of young men and girls. A youngish Jew in an overcoat and scarf, but no hat, is directing operations. Down the street another bustling crowd is building a barricade of paving stones. They are levered up with crow-bars and lengths of iron piping and dragged across the street until there is a four-foot-high barrier. Children come from the houses dragging odd junk—a bedstead, a few picture frames and packing cases. The whole is covered with a huge rubbish heap and out of that sticks a great bunch of chrysanthemums—a little faded perhaps, but very jaunty.

There is much shouting, but no disorder. Round the corner the carts are carefully overturned and packing cases broken up. The ground is a tangle of the thin iron strips used for binding them. They make a queer penetrating rustle as people pick their way among them. A shout for empty bottles goes up, and women come from every house arms full of oil stained, dusty bottles. Laughing they fling them down in front of the barricades.

“By God, they won’t come through here,” says one as she smashes half a dozen vinegar bottles on the stones.

When I pulled out a sketch-book to get down a few hasty notes for a drawing I was quietly surrounded. It was not through curiosity. There was a certain authority about the little man who asked:

“What are you doing here?”

I was a little nonplussed.

“I’m making a drawing.”

We looked at each other for a moment. One of those curious moments of recognition when you know you are speaking with a comrade. It is difficult to explain what it is, but just like you know a split when you see one, there is the opposite of that feeling when you know that someone is all right.

“O.K., comrade,” said the little man. “We have to be careful to-day.”

I went on drawing. Someone else came up.

“You go down the road, comrade. They got iron girders and all across the street there. You ought to get that one.”

That day everyone in the street was “comrade.”

A little way down the street I stopped and began to scribble again. Behind a barricade was a tight-knit mass of people. Just over the barricade—it was the yellow lorry—a solid mass of police was marching towards us. Looking down the slope into the oblique sunlight, you could see in the air a dancing mass of sticks and stones, The people of Cable Street were fighting for the freedom of their street. Moved by a single clear and determined idea—that Mosley should not pass—they were taking action with the only means at their disposal to make certain that the Blackshirts should not march through their world. Until they had thrown all the ammunition they had they stood in the barricade. Then the police came on and they turned and ran. But even as they ran before the blind rush of the police they knew the victory was theirs. They had fought for and established the freedom of their street.

We run in the street and along the narrow pavement. In front of me a man trips, falls and rolls over. His feet come up almost in slow motion until I see the soles of his feet. On one heel he has a circular rubber heel; on the other a worn screw where a rubber heel had once been. Round the corner people scramble through the barricade of carts and crates into the wood-yard. The police are running madly straight up Cable Street, then through the barricade, and we pull down the last packing case and close it. The police eventually—it seemed a long time, but it was probably only a few seconds—see the barricade and retreat hastily behind the corner. Then when there are enough of them they come through and chase us off the street.

The only way to Tower Hill was by a long detour by Gardiner’s Corner*, now partly cleared, and round the back streets. Petticoat Lane was half-way and people were shopping in a desultory Way. But there was a grim business-as-usual feeling about it all. Any other Sunday you might say these traders are out for a lark, and selling is just accidental. Today they are there because they have decided they ought to be there.

A policeman stopped me half-way down the Minories.

“Second on the left, sir.”

I guess it was my clean collar that produced the “Sir.” On Tower Hill there was a small, quiet, discouraged crowd. I set off up to Royal Mint Street when I heard the crash and roll of drums. Mosley’s private army marched dejectedly westward across Tower Hill. The people of the East End had won that Sunday’s struggle for freedom.

First published in The Eye Issue 7 Sept—Nov 1936

Notes

Mark Lane – A tube station on the Central and District Line, it was enlarged in 1967 and re-named Tower Hill

Mr Drages – Benjamin Drage ran a furniture store in High Holborn which specialised in hire purchase, all of which was delivered in plain, unidentified vans because of the perceived shame of being seen to resorted to hire purchase.

Confusion about clocks being wrong. British summertime, The clocks went back that day.

Gardiners Corner is the junction of Whitechapel Road and Commercial Road where there was a huge, wedge-shaped store until 1972 when it was destroyed by fire and the area became a traffic gyratory system.